A note about fictional languages and worlds

This blog post is a rough translation of blog posts I wrote about 5 years ago (which are, in turn, based on my personal notes on the matter), which I wanted to share with my English-speaking friend, only to find out that it should be translated from Russian first. So here we are.

I am not an expert in history or linguistics. But I’m very enthusiastic about these topics, and I also love writing stories and creating fictional worlds (and also helping others with this). And that’s basically the story behind how the original notes were born.

Usually all my notes are structured as chaotic mess of bullet points, and these were not exceptions. So while it’s not a very comprehensive and complete guide from an expert in the field, you can sort of see the general thought pattern behind all this.

Most of the text from this point onward will be a more or less direct translation of the original blog posts. There might be some additional information or corrections, but it’s probably going to end up mostly the same (and any changes I’ll end up making will probably be reflected in the original posts as well).

about fictional languages

here’s the link to the original note btw

It is worth mentioning right away that I am not a linguist and am generally not that deeply immersed in the topic. It’s just a hobby of mine to study the history of languages and the connections between them at my leisure.

This whole post started when I started reading articles about Proto-Indo-European (hereafter PIE) a few months ago. At the same time, I was watching the latest season of The Expanse, a TV series based on James Corey’s books from the series of the same name, and those books are famous for their elaborate history of the world and what one would call “authentic” languages. Those two things are what gave me the idea for a post like this: I just started writing down a note with “rules for creating believable language” as I went along, and this blog post is a slightly cleaned up and better structured version of the note. And, yeah, as you can imagine, this is just a note with my observations on the matter. Given everything I’ve mentioned above, it should be fairly obvious that this is not an expert opinion, there may be many strange examples or mistakes, but I don’t claim to be the truth in the first instance.

Actually, there was another factor here: the Star Trek universe, which led to another curious thought. I’ve rarely liked fantasy worlds because they rarely boast any kind of authentic language or elaborate story (well that’s an exaggeration, but you probably get what I mean). There are exceptions, of course, and they tend to be big and important works (like Tolkien’s Middle-earth saga), but specifically the problem with languages in general is not even unique to fantasy settings.

Corey did it best in The Expanse, in part because the history of his world and the languages in it are based on real life history. It’s always easier to build off of such a base, and it always makes a lot more sense in our heads and adds a lot of missing details.

And that’s probably the moment to share the rules/common themes I noticed, but first I have to list a number of additional things that I noticed sometime later, after the note was complete. They don’t fit into the main rules, but they complement them and should act as a foreword of sorts.

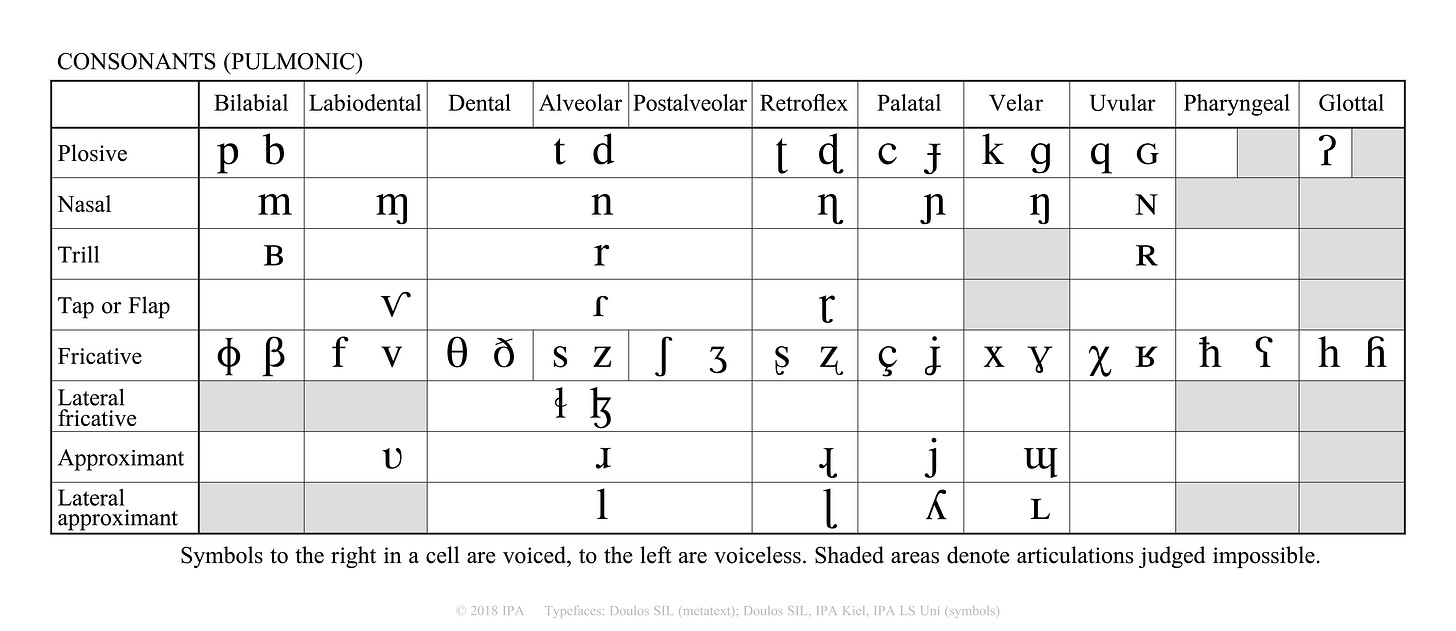

The process of language creation should start, first of all, with the history of the world. And the deeper you go, the more authentic everything about it will be (and at the same time it may sound more and more alien). One of the most important bases of the created language will be a kind of pronunciation table — and here you should also stick to some balance (you can find lists of phonemes and pronunciation tables on wikipedia, or you can just google it), but if we want it to feel more authentic, this table should be filled out based on the environment and historical changes. It’s also important to remember that a real language will not have a perfect phonetic system.

The basic sounds of a language are formed by imitating the environment, describing phenomena by imitating their sound (e.g. the word for river would be created by combining sounds, which are similar to “flow”). In this way, the basic sounds and basic concepts that emerged first in the proto-language can be formed. In the future, phonetics changes with the environment and movement of speakers across territories, as well as in interaction with other peoples living in another territory and having their own basic concepts and phonetics. And over time all the languages tend to get simpler: less sounds to work with, shorter words, etc.

UPD 18:34 20.04.2020:

After posting this note, I thought about one more thing: the change of living conditions and landscape over time. During the existence of modern man, there were two ice ages, a number of areas were flooded, and some areas were either covered with ice or, on the contrary, they got rid of it.

Rock paintings and other traces of human life have been found in the Sahara, and research has shown that the Sahara was not once a desert (but rather like a savannah). The Arabian Peninsula was much more strongly connected to the mainland. North America and Asia were once connected with a landbridge, which people used to travel and subsequently became the local indigenous population. North America was covered with ice for a long time, and when the glaciers began to melt, large lakes were formed (one of which is now the Great Lakes).

Well, the actual details might not be that accurate, but you’ve got the core idea.

Many examples can be given. The point is that the living conditions and environment at the beginning of language formation, its phonetics and basic words, can be quite different than at the beginning of the path. The actual foundation, however, will change less willingly, just as people will be less willing to change their place of residence, so that (1) words uncharacteristic for the place of residence may somehow end up in the language of local peoples (e.g. words for water, rivers, lakes, different vegetation in the desert) and (2) part of the population may go in search of a better life to other parts of the world, so that some of the culture and language may overlap with other peoples over time, even if they lived at different ends of the world (although of course, in the case of complete isolation, it would be difficult to maintain such links, so if people were isolated from the “outside world”, as was the case with, for example, the inhabitants of the Americas, the differences in culture and language would accumulate much faster and make them completely different compared to others).

/UPD

And, funnily enough, a similar effect can still be achieved by iterating on some “base” from the formed history of the world.

The “base” can be some point in the real world history. Or it might be abstract ancient time of a fantasy world. Or it might be an even more ancient history or a made up world, starting before the first human-like creature appeared through evolution. The closer the starting point is to our current point in time, the easier it is to construct something out of it (and it’s also easier to write a story around).

That’s how the sounds and basic concepts of proto-languages blend together. And as long as the standard of living is low enough, and there is no concept of history and writing б languages develop rapidly, mixing with each other and changing towards simplification.

And here I will start listing points from my note, with a short remark on them afterwards.

If the events take place within a small territory that is more or less coherently composed and is closed, one can try to work out a proto-language to start with. In a more or less open environment, however, a single proto-language makes no sense (reasons above).

Over time, the same roots and words can and do change meanings (example: “hour” can mean “time” and can mean a unit of time).

Languages are constantly exchanging words, especially if there is already some form of trade in place.

Names of inventions are almost always borrowed (UPD: Names of plants and animals that are characteristic of another area are also borrowed or created. And often these names can become very distorted. E.g., the word “slon” (note: elephant in Russian) comes from the word “aslan”, meaning lion (how did that even happen?), and the word “apelsin” (“orange” as a fruit in Russian or Swedish) comes from “apple”, which used to mean not an apple specifically, but any fruit, and “cin” in turn probably points to China (and is also a distorted-sounding borrowing of the name). Another example of distorted borrowing is the name for China itself in Russian (and some other languages) — “Kitay”: it goes back to the name of the Khitan people, who were nomads living in the region and who eventually settled in a province in China towards the end of their history, but it was these nomads that Russian ancestors encountered much earlier. That said, the name of the people itself has many variations in pronunciation from nation to nation due to local phonetic peculiarities).

Significant divergence of languages usually takes about 150 years, although it also depends on living conditions, writing and the speed of succession of generations. Usually the rate of language renewal is not very high, but in case of rapid succession of generations (including times of cataclysms or encounters with more advanced people) the language changes faster.

Strong dominance of a language over different territories leads to the emergence of simplified versions of languages: pidgins and creoles. Usually the existence of such languages is closely related to the low level of education of the speakers. Often simplification occurs both in the structure of the language and (mainly) in vocabulary: there are fewer exceptions and borrowings, and various complex words are replaced by simpler compound analogs, or become a more streamlined in terms of meaning (“boss man” → “bosmang”, meaning “captain”, in Beltalo’da from The Expanse; another example: “for the good” → “fodagut” meaning “please”).

The changes of a language over time depend on living conditions, neighbors and global events: there are so many factors that it is hard to keep track of them all and we can roughly say that changes are chaotic (more chaotic if one of the factors is stronger: e.g. a low standard of living contributes to a higher rate of language change and faster, “chaotic” changes). It doesn’t mean that all the changes are chaotic, but with the complexity it becomes harder to keep track of all the changes.

Conditions can shape the phonetics of language (and subsequently writing): what is easier to say for the locals will be reflected in the language.

As soon as education begins to develop and writing spreads, language changes begin to slow down. As soon as the concept of people’s identity appears and the language gets some standardized form, the language becomes almost static.

However, depending on the type of writing, the changes may become stronger or, on the contrary, remain at the same level.

The writing of one language can pass into another. It will not necessarily work well, often it will be used mostly for similar sounds, but the correspondence in phonetics may be incomplete. This will entail a change in the writing system itself and its adaptation, or a change in the language.

Object writing → pictographs → hieroglyphs (simplified pictographs) → transition to the use of hieroglyphs based on consonance and their simplification for cursive writing → alphabet and its borrowings (by alphabet I also mean abjads/abugidas).

Alphabets that originated from the same source will not always look exactly like the original source (example: Latin, Greek, Cyrillic, Hindi and ancient Egyptian script are relatives), and there can be many ways of borrowing. In some cases, the existence of a writing system may be inspired, but the system itself may be created from scratch (Hangul).

Swear words are closely related to the cultural context and the most important concepts for native speakers, the more important — the heavier the swear word is (examples: mother of God, sexual imagery in the context of plowing the land and the natural fertility cycle, fertilizer).

If a society is sufficiently developed and has moved to the stage of globalization, after a long period of time the influence of languages on each other will inevitably make them very similar, with differences in basic vocabulary and phonetics. This will not lead to a “single language” necessarily, but there will be sort of waves of convergence.

Religion and mythical imagery come from speaking names and basic vocabulary. The roots of the names of gods can go far back in time (PIE “sky” and “sky god” → Greek Zeus, though it is better to google Proto-Indo-European culture and connections between gods in different cultures, there are a lot of peculiar connections), in different cultures with a common root will be similar motifs, stories, myths, images. The names may change places, distort, but the similarities will still be perceptible.

The existence of a large empire (like the Roman Empire) blends cultures into a single mixture and makes cultures adjacent in all connected territories, spreading a lot of common vocabulary, stories and concepts (so the names of gods can come from another language, although the gods themselves were there before).

The names of gods and phenomena influence things related to the daily course of life , including time and the calendar. For example, the names of the days of the week in English are linked to the names of celestial bodies and gods, in Slavic languages to the general order of days and routine, the names of months in Latin originally began with March and were simply numbering, but later received the names of personalities and shifted by two with the addition of new months, in Slavic the names are linked to the seasons (and gods through characteristic “speaking” words), etc.

Building one credible language in a fictional world (even if that language and world are based on the real one) requires thinking through the HISTORY of the world in the first place. Language, its structure, function, and everything else is directly dependent on the historical context. Without world building, there is no valid language

The order of words in a language (SVO / VSO / OSV / …) is independent of family and parent, can change later. Initially it is best to stick to optional word order, but idk.

The unique features of languages (endings when addressing others, ways of word formation, conjunctions and sentence construction methods) are similar within the same family. In a long run they may be based on some slight variation.

Names and titles (of settlements, things, etc.) are based on important concepts and names of gods. Names may be distorted and passed from language to language.

The narrative is told through the lens of the characters and their thoughts. We don’t see their language or hear it, but language can be shown through writing, through other people’s languages, and through names.

The older the language, the more gimmicks, exceptions, and strange constructions that don’t belong (English phonetics and writing). Pidgin languages based on an older language will be cleaner and simpler. Likewise with loanwords, they will be cleaner after being adopted into the new language. That said, the languages tend to get simpler over generations.

Once the history of the world, language, its speakers, phonetics and everything else has been thought through, there is only one thing left to do — to repeat the process over and over again, to polish the result, to iterate and simplify. You can choose one historical period (e.g. the rise of the Roman Empire), think through the history up to this period and take the languages in this time point as a basis, and after that — repeat the process, move 50–100 years forward at a time, simplify the languages and impose on them the influence of events and neighbors. The earlier in time you start, the more authentic everything will be perceived.

Well that’s about it. In general it would be interesting to read comments on this topic and develop the ideas further, so I invite knowledgeable people to comment.

The main problem with these notes is that I don’t know where to apply them further (well, maybe there is one small idea, but it’s a long way off). But if they are useful to anyone — please, let me know.

P.S. IPA phonetic alphabet table

Foreword

…well this is awkward

Initially I wrote translations for both of my notes, but after finishing it, decided that (1) it will be too much and (2) the 2nd note about “history pattern of a fictional world” sounds a bit naive and dumb now.

I still like this languages note, but don’t really want to mix it with the other thing. Plus otherwise this blog post would be like 30 minutes read time anyway.

So that’s it I guess? Share your thoughts, will be happy to make additions to this note.